What will Harvard students do this Fall?

Responses to the Fall 2020 policy and plans for the uncertain future.

At a glance

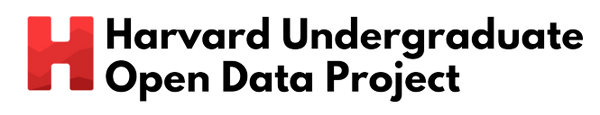

- 70 percent of students are at least somewhat likely to enroll, and 15 percent are extremely unlikely

- First-years approve of Harvard policy more than upper-class students

- 40 percent of off-campus enrollees will try to live with Harvard friends

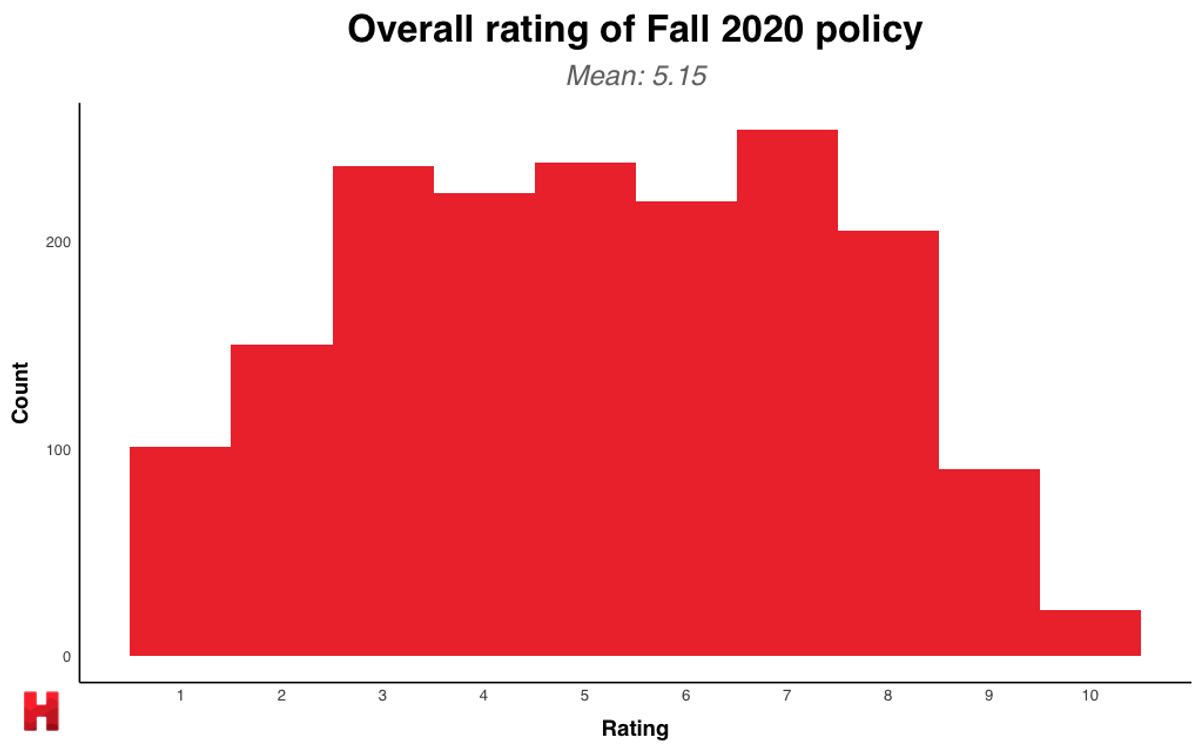

- Majority of students are unhappy with the plan overall (average rating of 5.1/10)

- Students who predicted more people in their year would enroll are likelier to enroll

- Most students want more assistance for students on financial aid

On July 6th, Harvard students woke up to an all too familiar sight: an email from the administration with a major announcement about Harvard policies regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. The administration announced that the Fall 2020 semester would be taught entirely online, and that only incoming first-years and a subset of approved upper-level students would be allowed to return to campus. Everyone else would spend another semester learning remotely, with seniors prioritized to return in the Spring.

We at the Harvard College Open Data Project wanted to see how students reacted to the new policy. We sent out a survey to the student body on the evening of Tuesday, July 7th, one day after the announcement, that ran until the evening of July 11th. In total, we received 1766 responses, which represents just above one quarter of the undergraduate student body, including incoming first-years. Here is what we found.

Who is coming back?

With the majority of students not allowed to return to campus, and with heavy restrictions in place for those who are, many students are considering taking the Fall semester off and returning when things are more normal.

The results also heavily differed by class year, with first-years significantly more likely to enroll than upper level students. (The high enrollment of first-years could be because they are the only class cohort allowed on campus in the Fall, because incoming first-years have already had a chance to defer, or some combination of both.)

Our sample had considerably more incoming first-year respondents than respondents from any other class year, so we re-weighted the responses based on how many students are actually in each class year.

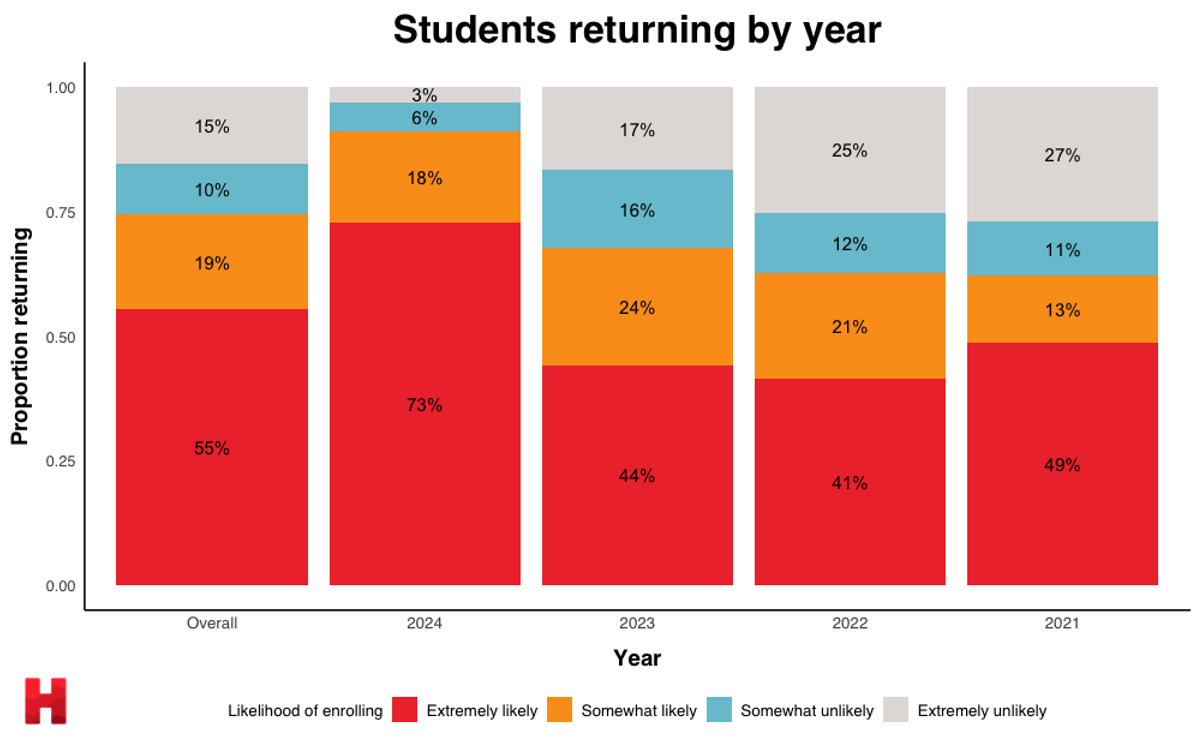

We also examined enrollment likelihood among international students and based on financial aid status. The same day that Harvard announced its policy, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced that international students would not be allowed to remain in the United States if courses at their school were entirely online.

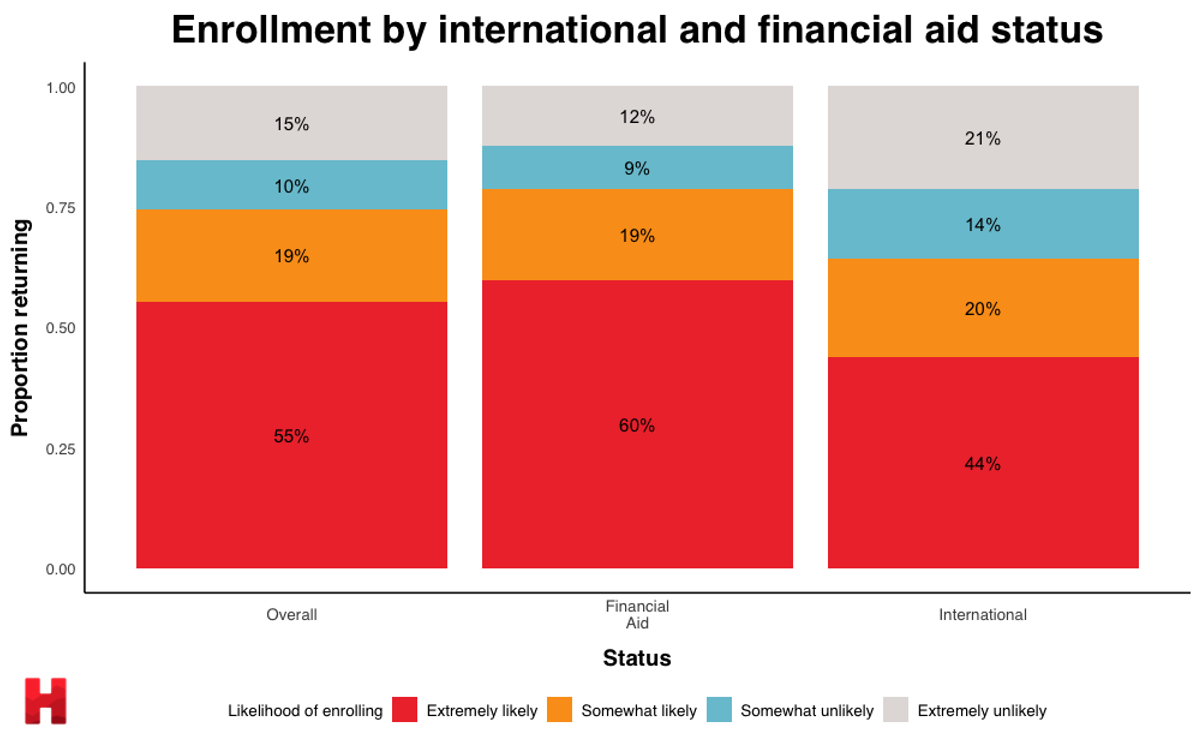

To get a slightly better estimate of fall enrollees, we conducted simulations assuming that 99 percent of “Extremely likely,” 75 percent of “Somewhat likely,” 25 percent of “Somewhat unlikely,” and 1 percent of “Extremely unlikely” respondents would enroll in the Fall. Our simulations predicted that around 68 percent of students would enroll.

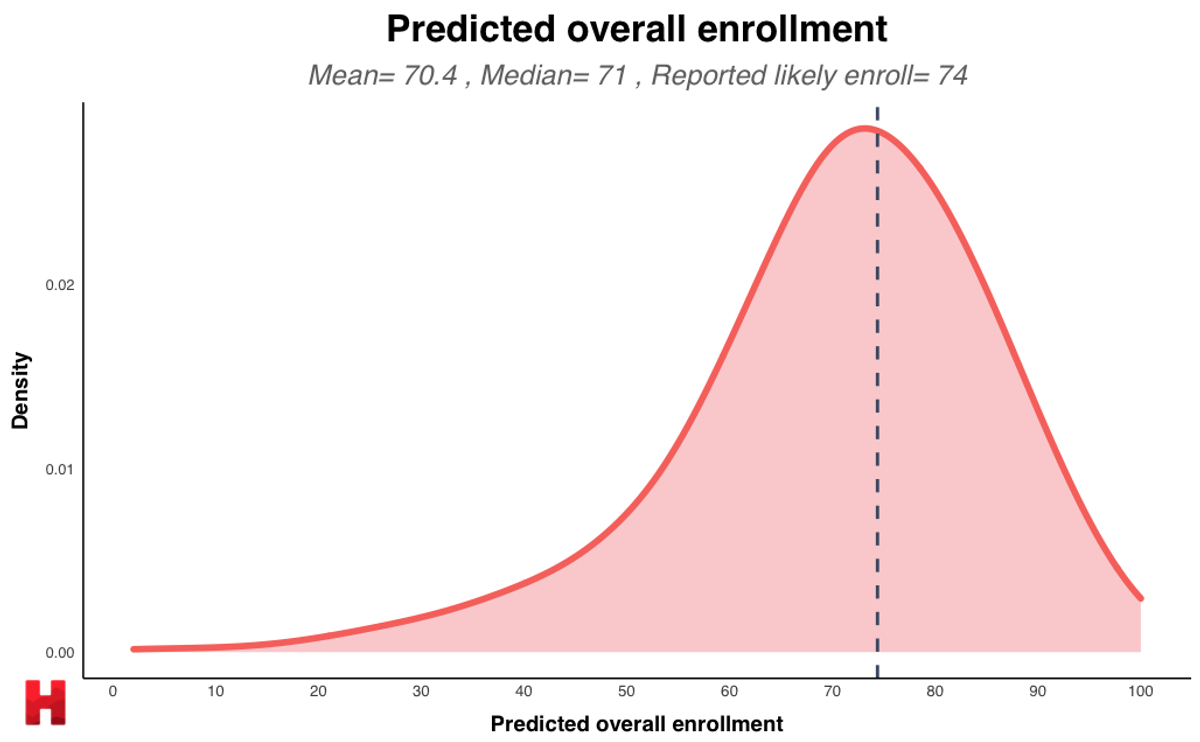

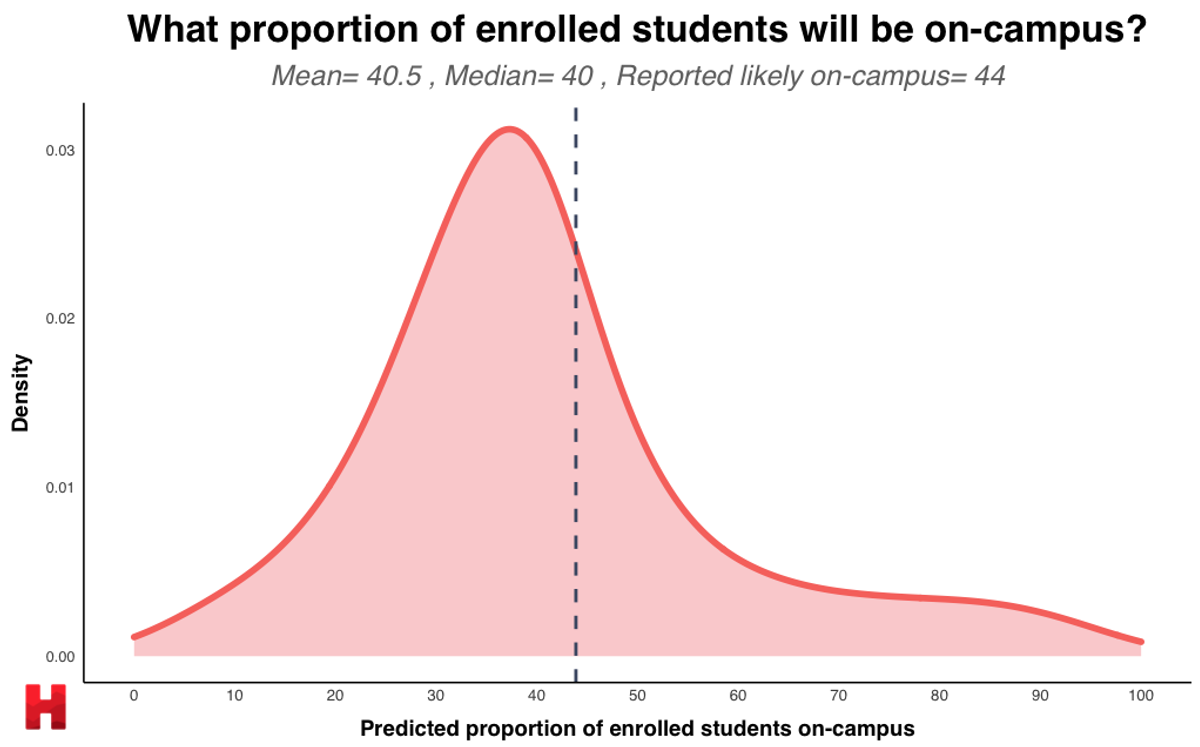

Another way of trying to gauge the percentage of students who will enroll is to use the wisdom of the crowds, so we asked students what they predicted the overall enrollment would be. The average prediction was around 70 percent, which is exactly the reported proportion of students likely to enroll after re-weighting for class year. The distribution of predictions is below, with the dashed line representing the (unweighted) proportion of respondents who said they were extremely or somewhat likely to enroll:

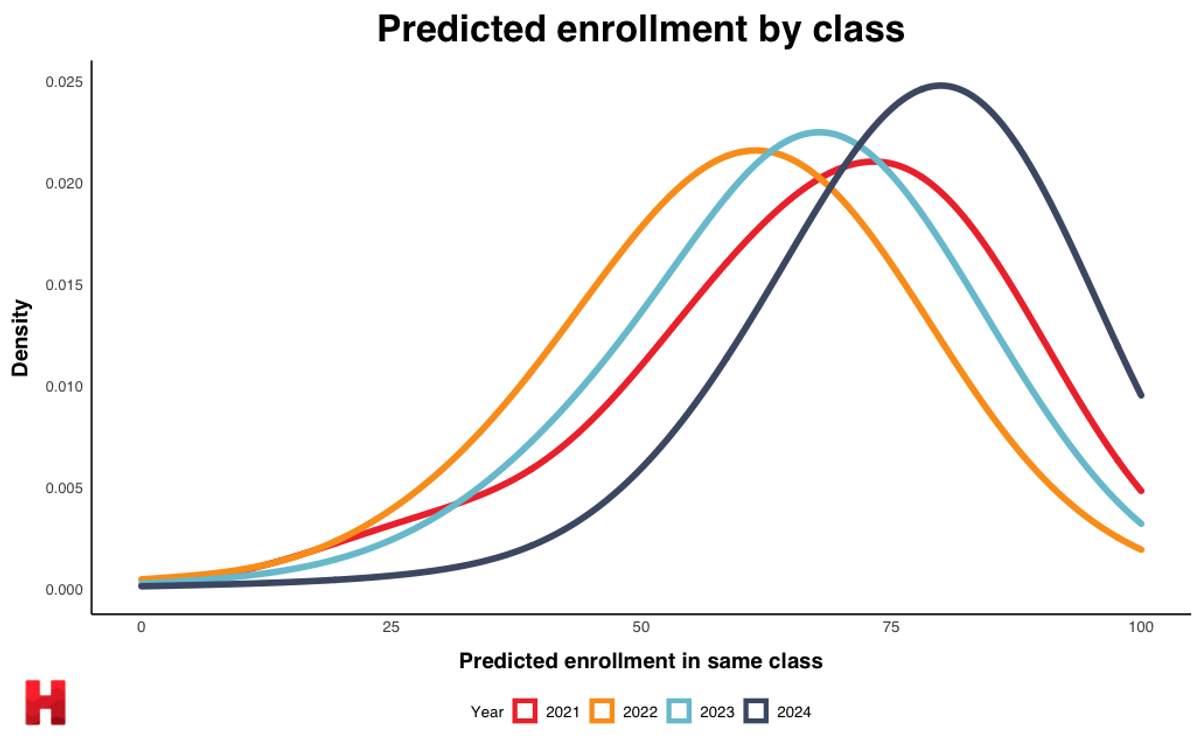

We also asked students how many students in their class year they thought would enroll, and once again, the results are more or less consistent with what students were reporting about their own enrollment:

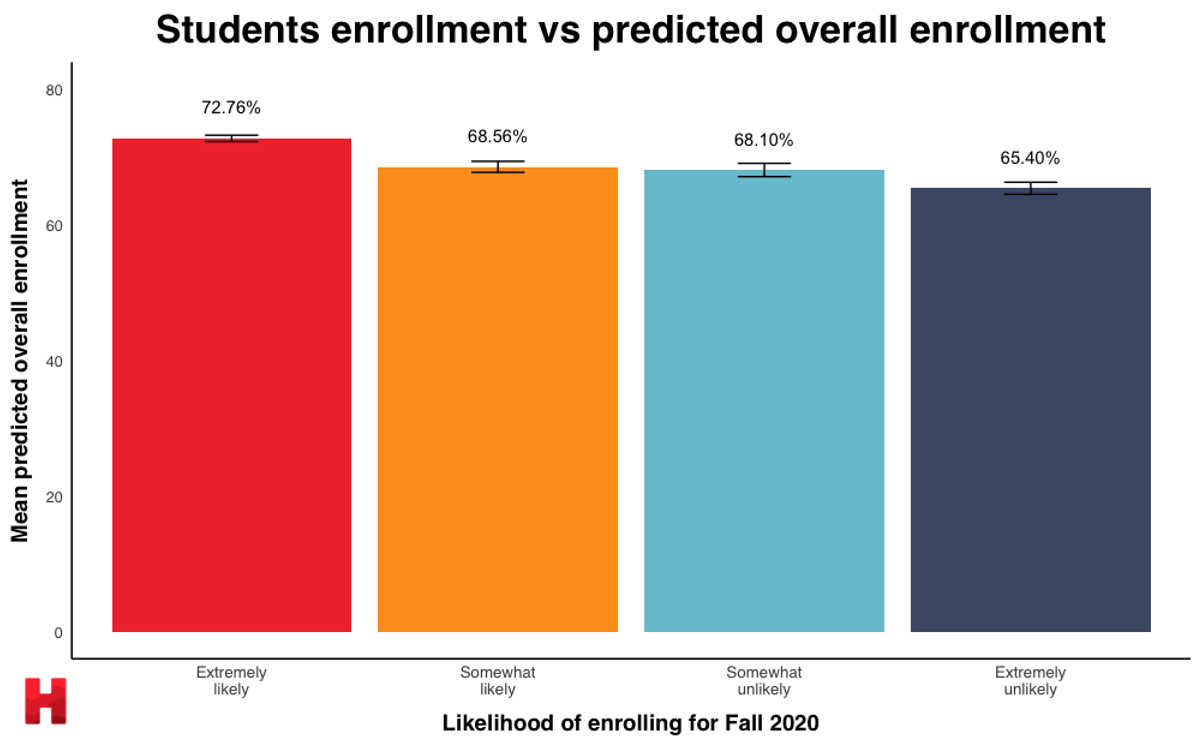

One interesting point that we found in an earlier analysis was that students were most likely to enroll if they thought their friends would enroll. We tested that prediction by comparing a respondent’s individual likelihood of enrolling to the proportion of students they predicted would enroll in the fall. We found that respondents who thought a greater proportion of students would enroll were more likely to enroll themselves:

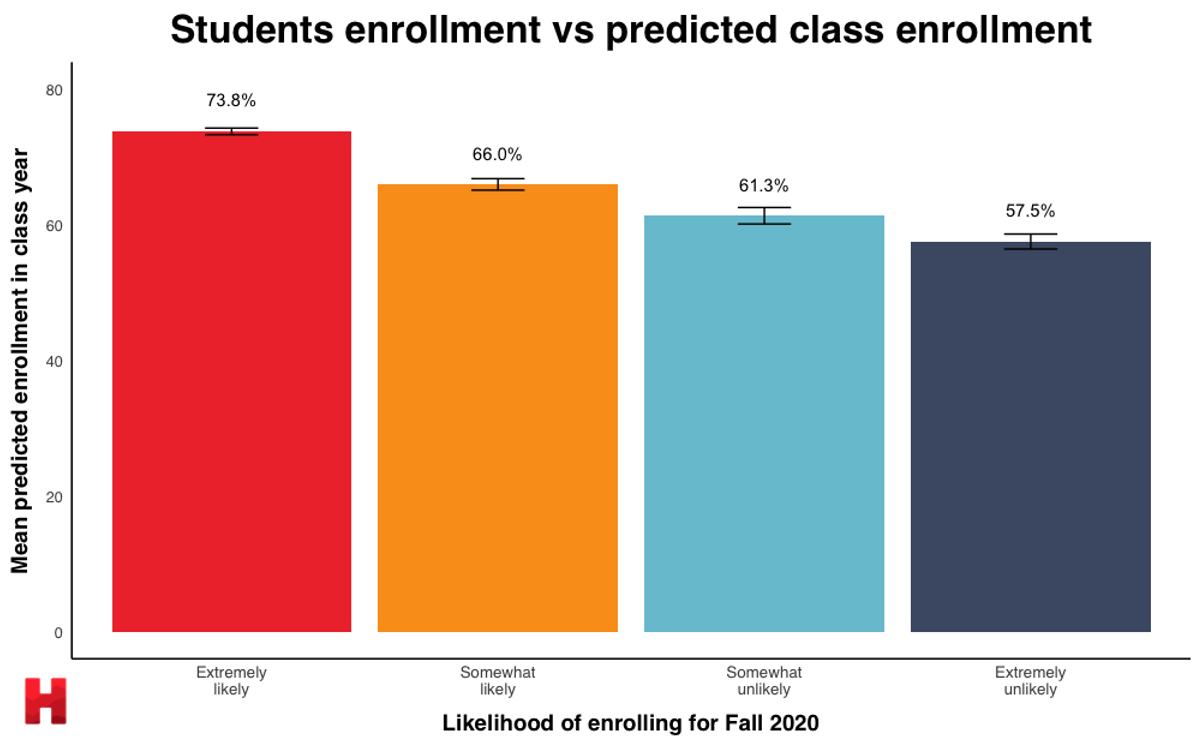

The relationship was even stronger when comparing individuals’ likelihood of enrolling with the share of students they predicted would enroll within their class year. This makes sense because most students likely want to stay with friends in the same year, so students who think most of their friends are not coming back would also be less likely to enroll themselves:

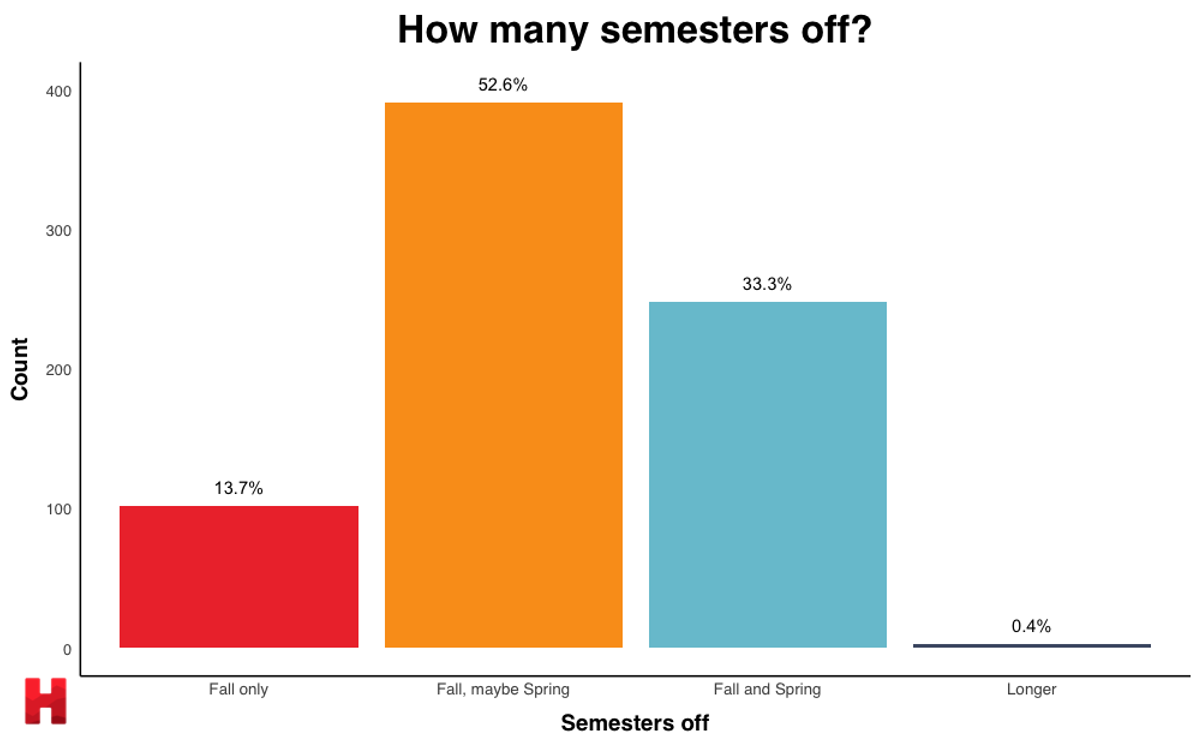

With many students considering taking time off, we wanted to understand if they would only take one semester off, or an entire year. For the most part, students who were considering taking time off said they would take the Fall off, and then wait and see for the Spring. However, around a third of students reported that if they took time off, they would plan to take the entire year off rather than just one semester:

We also wanted to see what restless Harvard students might do if they took time off.

Only 3 percent of students said they would “Chill at home” without seeking other opportunities.

On campus or at home?

While only incoming first-years were guaranteed to return to campus, Harvard is allowing upper-level students to petition to return to campus under certain circumstances. 19 percent of upper-class students reported that they were planning to petition to return.

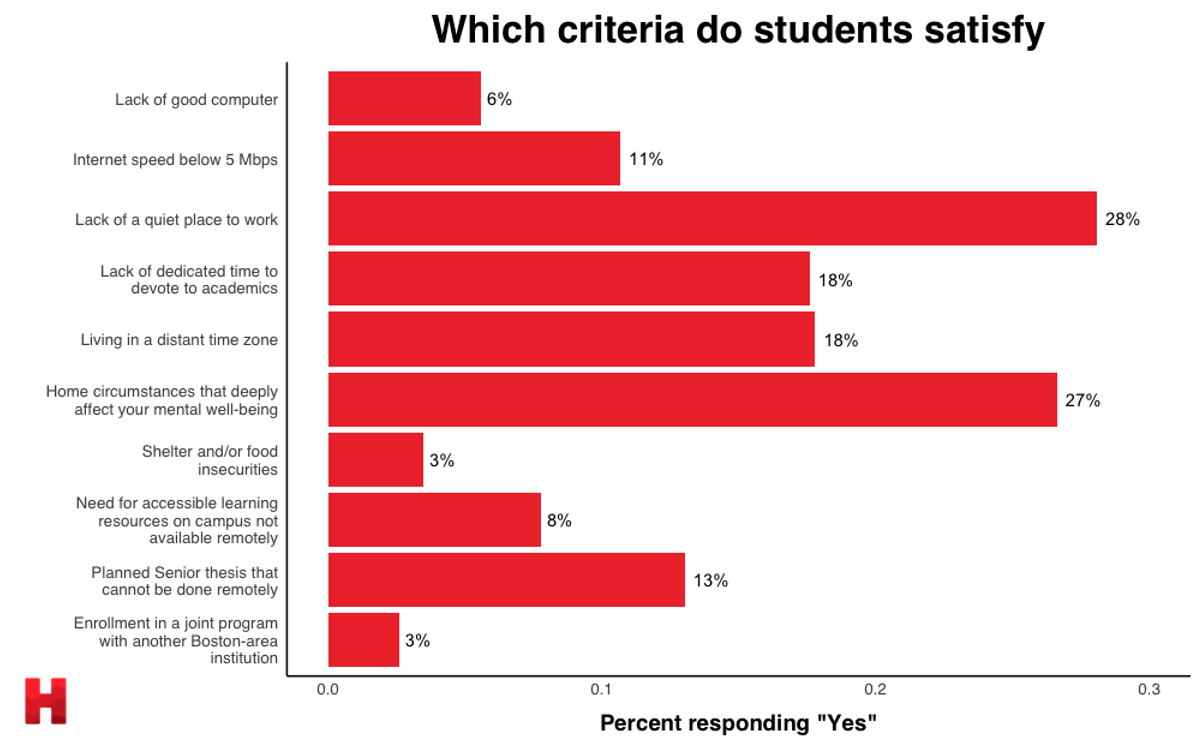

Under Harvard’s petitioning process, students must indicate which criteria for needing to be on campus apply to them. We posted these same criteria in our survey, and found that the most common criteria satisfied by students had to do with mental health or difficulties working at home:

42 percent of students indicated that they would not satisfy any of the criteria, with an average of 1.26 criteria satisfied per student.

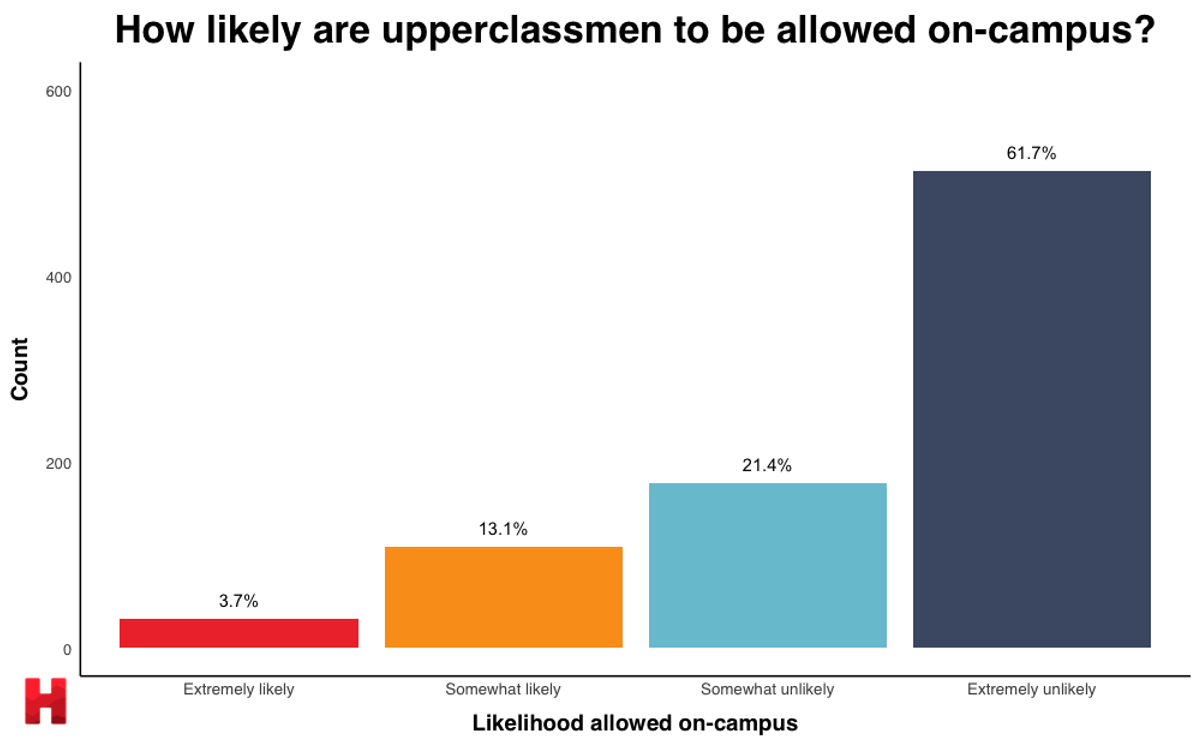

Students were generally pessimistic about their chances of returning. Among upper-class students planning to enroll, upwards of 60 percent thought that they would be extremely unlikely to be eligible to return.

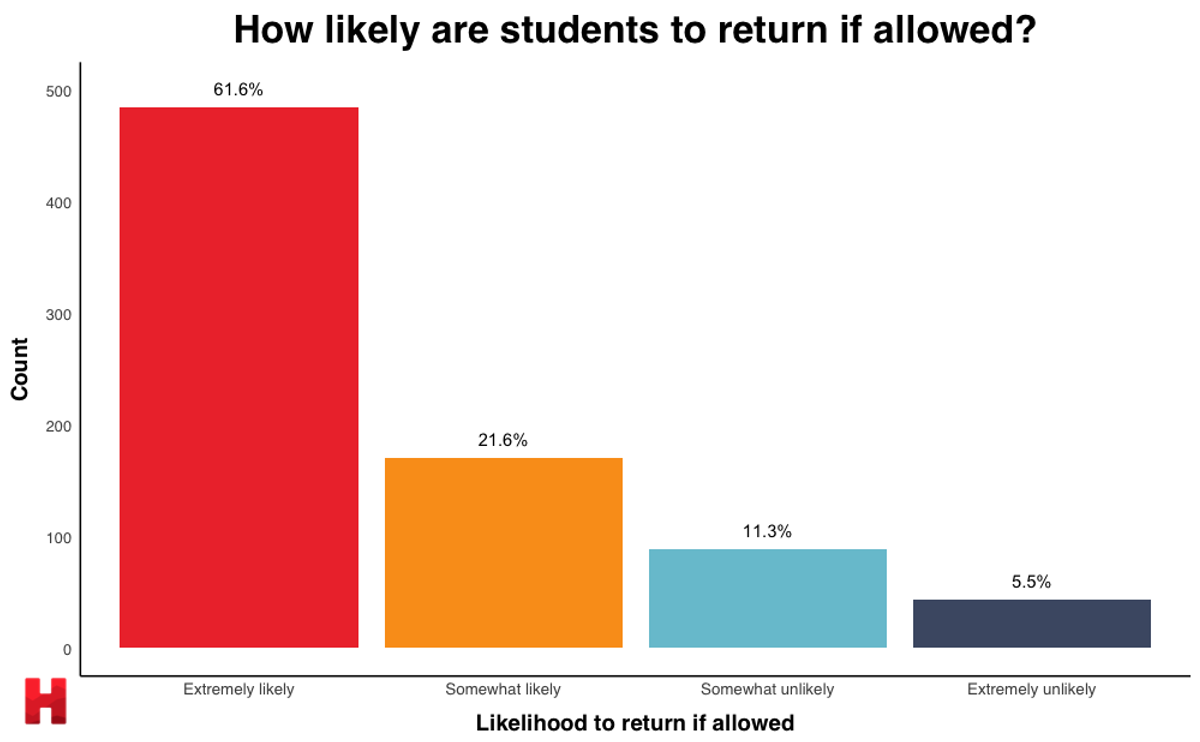

Most students however, would be happy to return if given the chance. Over 80 percent of all respondents said that, if eligible, they would be extremely or somewhat likely to go on-campus in the Fall.

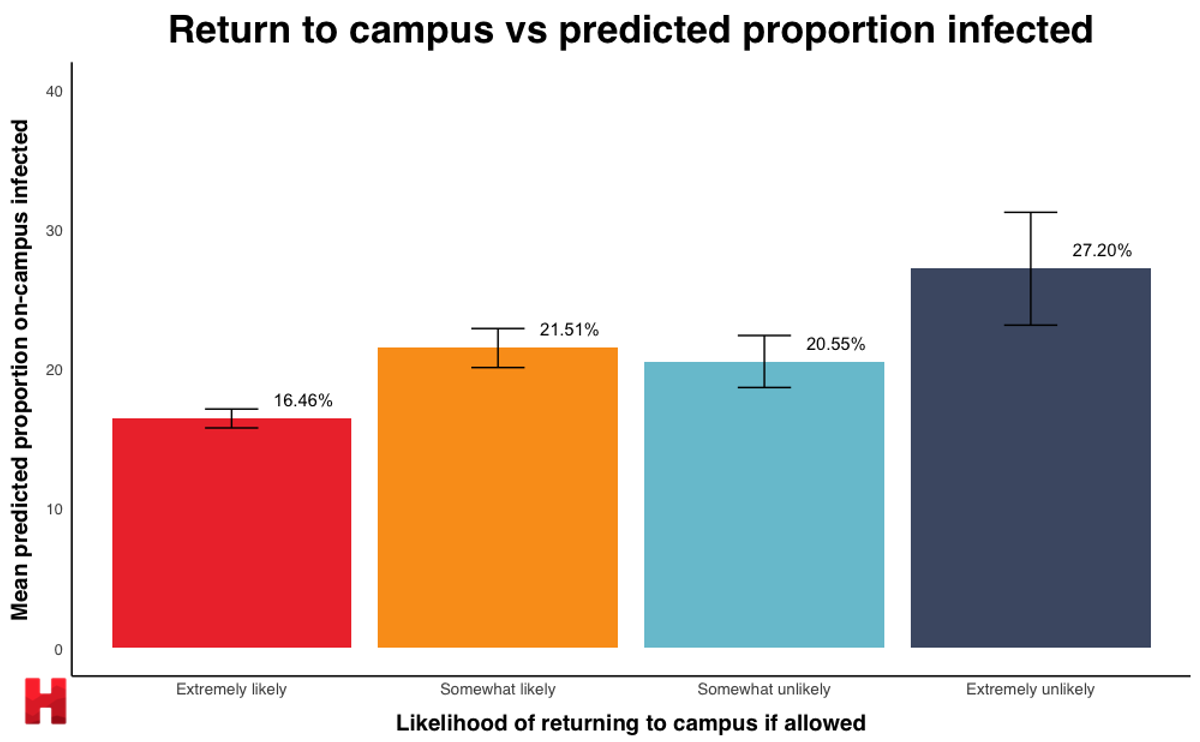

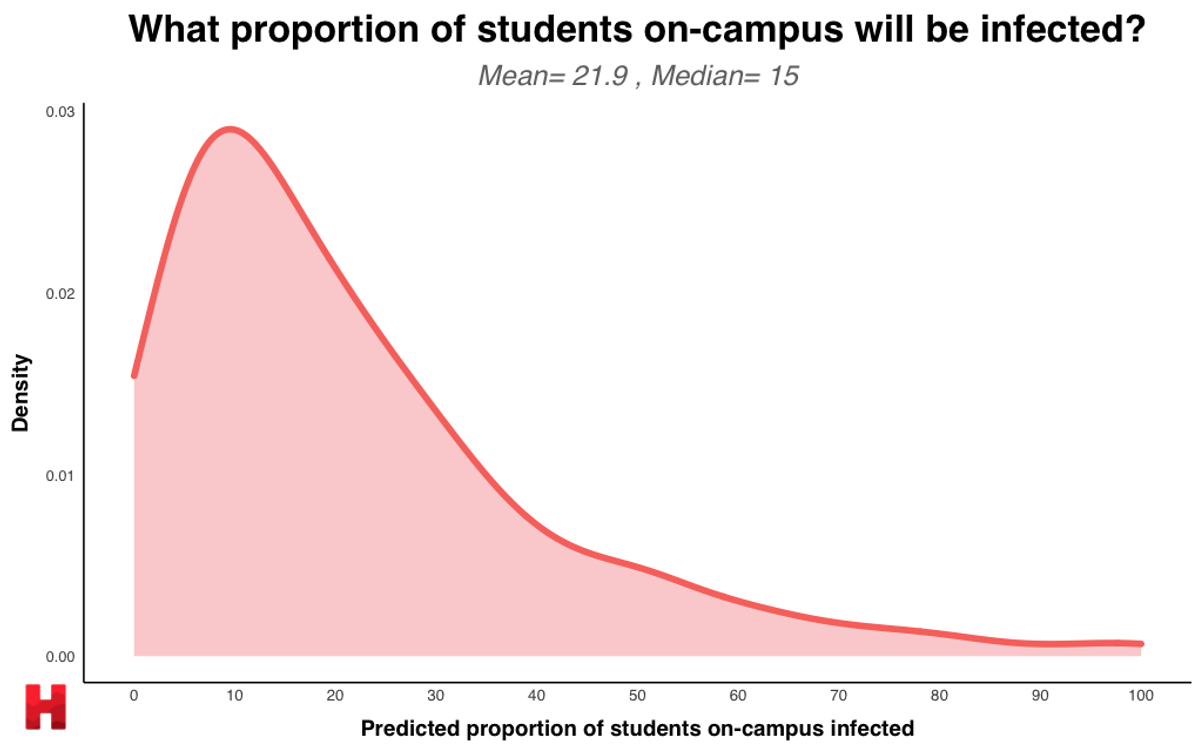

To gauge whether students were more likely to return if they thought the risk of infection was lower, we asked students to predict what proportion of students on campus they believed would be infected by COVID-19 during the semester. We found that students who were more likely to return if allowed had had a lower perception of the risk of infection from COVID:

We also asked students to predict how many students would actually be on campus among those enrolled. On average, students predicted that 40 percent of enrollees would be on campus, compared to 43 percent of students who reported that they would be enrolling and likely on campus in our survey. This was about on par with the administration’s stated intention to bring back 40 percent of the student body on campus:

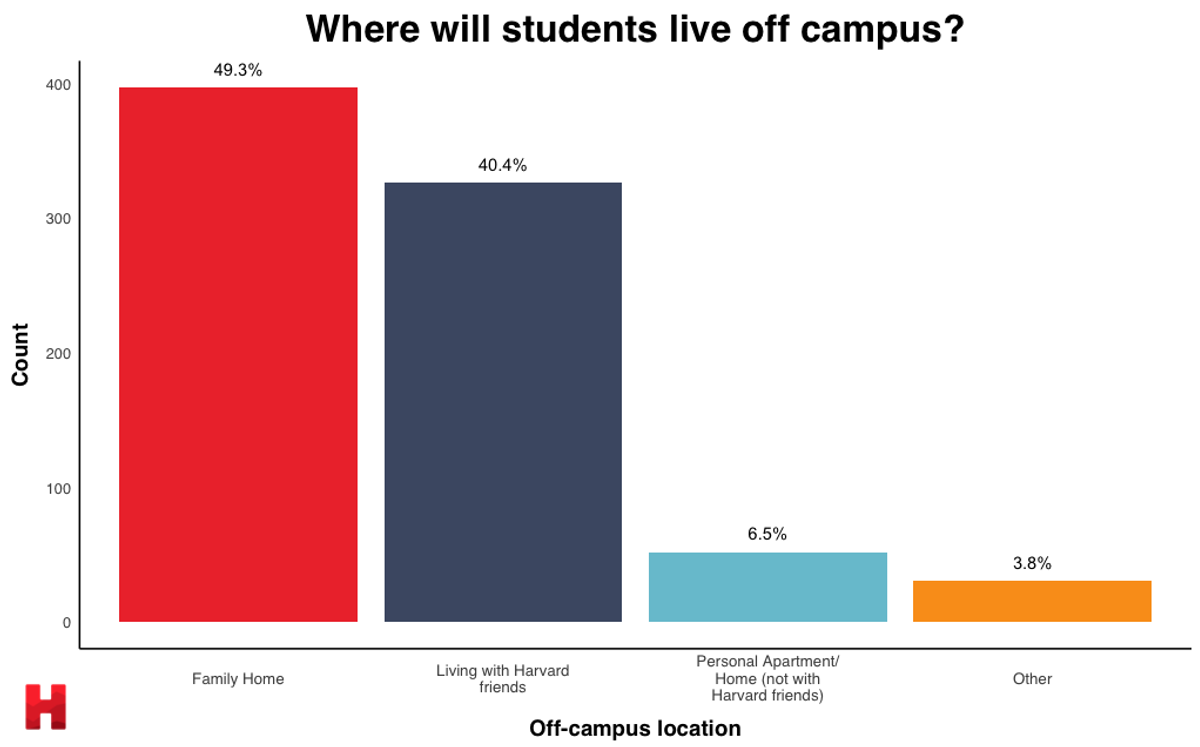

Finally, we were curious about where students would take classes if they were not allowed to return. Many students had discussed renting apartments or AirBnbs to live with friends during the semester. Though 85% of students in an earlier survey reported living in their family home after leaving campus in March, we found that only half of students planned to take courses from a family home in the Fall.

Overall reactions

This survey was by far the most popular survey that HODP has ever sent out, likely due to the fact that students have strong opinions about Harvard’s policies.

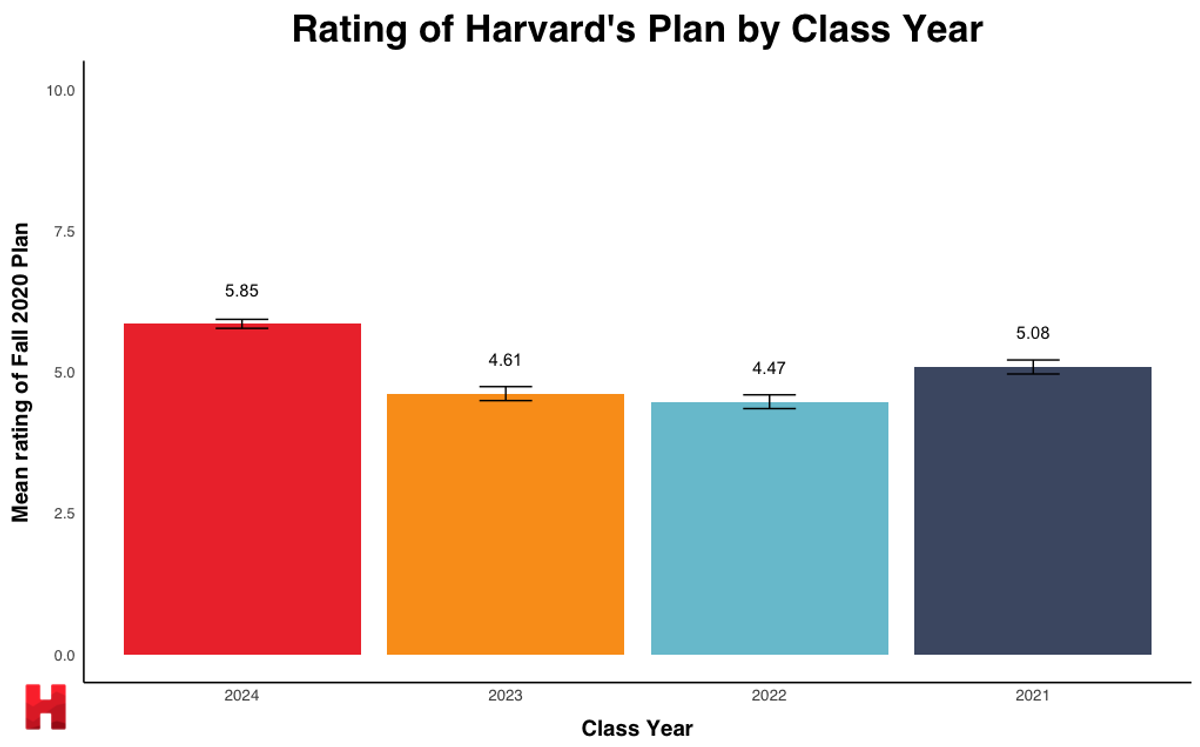

Unsurprisingly, first-years, who are allowed on campus in the Fall, rated the Fall plan a full point higher than the next cohort. Seniors, who are slated to be allowed back in the Spring, were the next most approving.

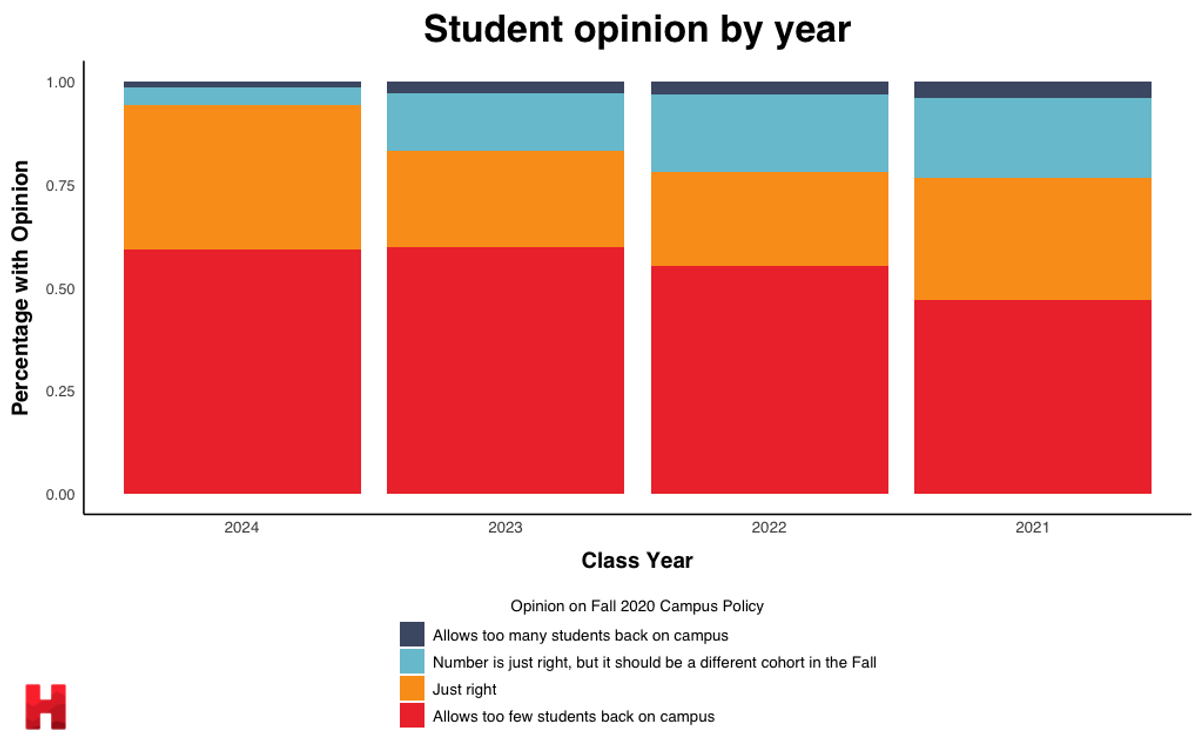

Most respondents felt that too few students were allowed to return to campus, although disaggregating results by year shows a number of upper-level students agree with the number of students allowed to return, but thought a different cohort should have been chosen in the Fall.

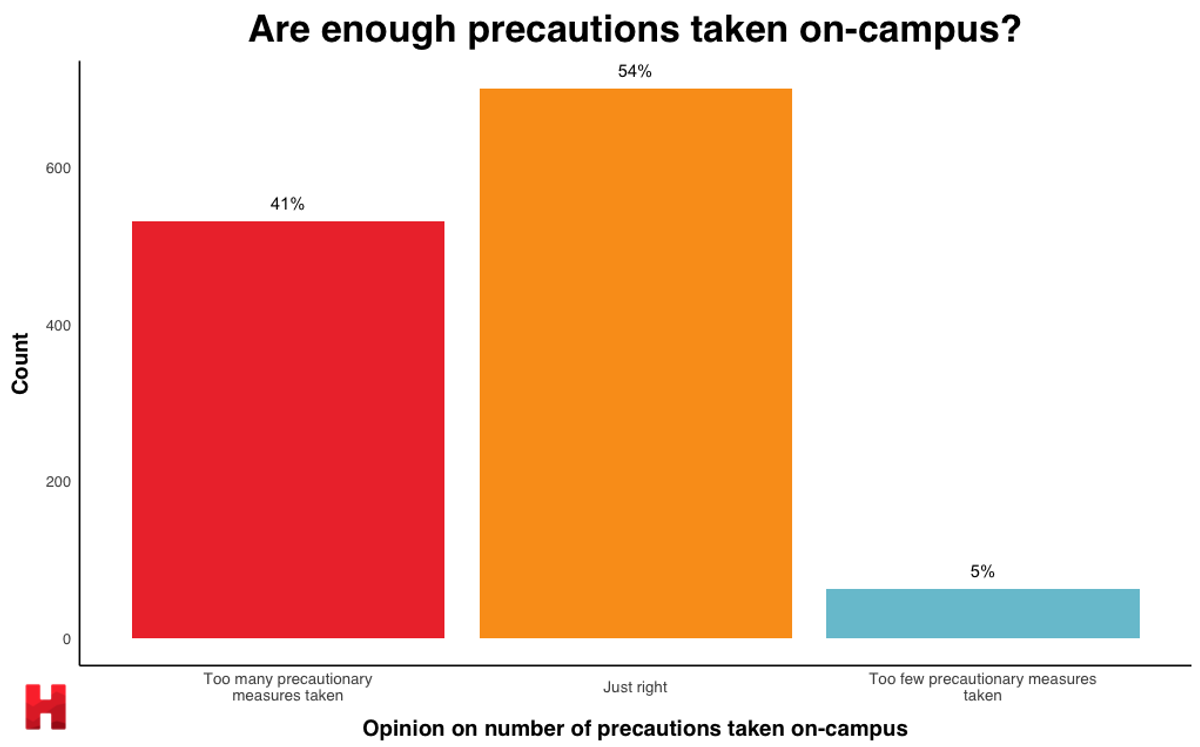

Students were more satisfied with the number of precautionary measures taken to protect on-campus students, which includes testing every three days and heavily restricted movement. On-campus students will have swipe access only to Harvard University Health Services, their dorm, and one assigned dining hall. No guests (including other Harvard students) are allowed in dorms.

We can gauge how effective students think these precautions will be based on how many students they think will be infected during the Fall semester. The distribution was right-skewed, so the mean prediction of 22 percent was considerably higher than the median prediction of 15 percent of the on-campus students being infected by COVID-19.

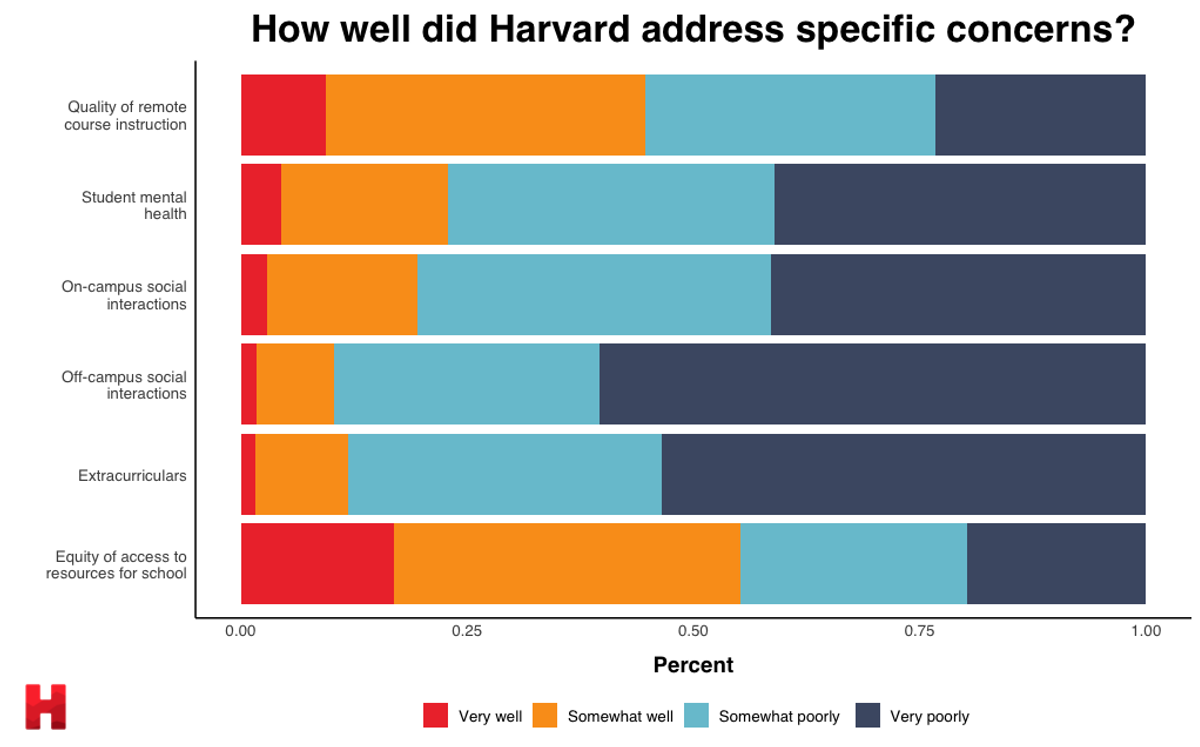

In addition to announcing the policy on returning to campus, Harvard also announced that they would take measures to address a variety of concerns students had with another virtual semester. For the most part, respondents were most unsatisfied with how Harvard addressed maintaining social interactions both on and off campus, but thought the administration did a better job addressing equity of access to school resources.

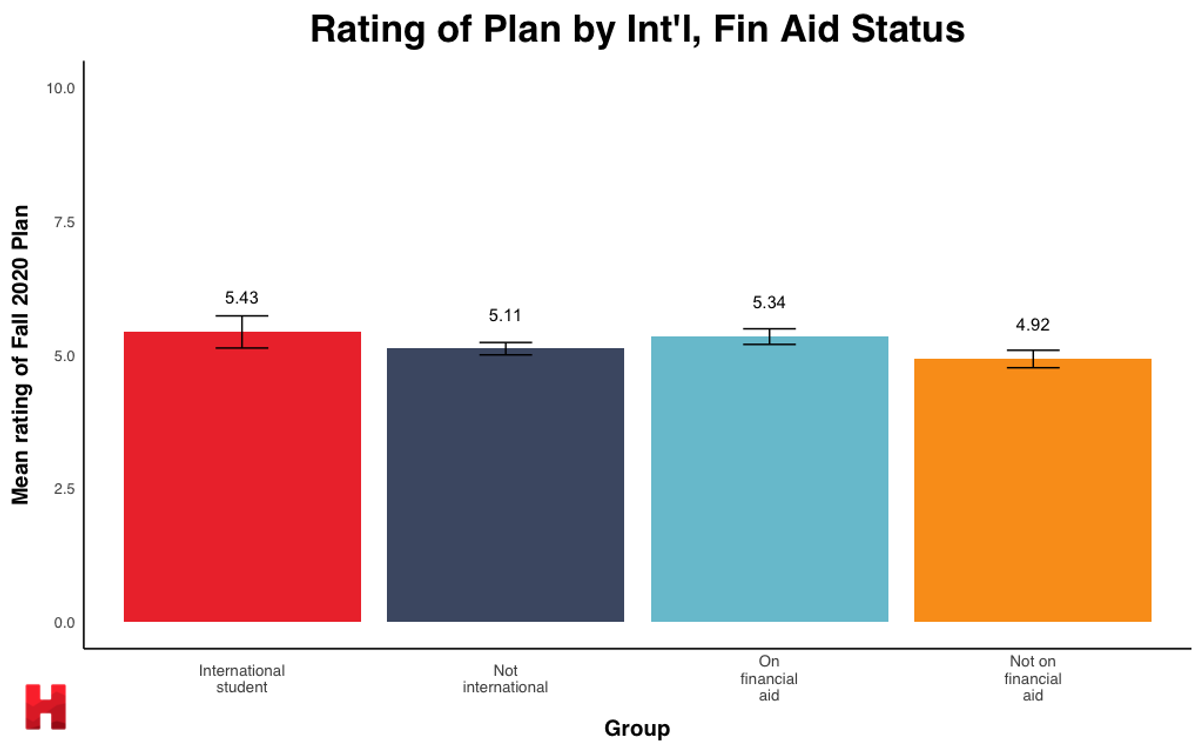

We were also curious about how international students or students on financial aid rated Harvard’s policies. We did not survey students on the ICE order or how it affects Harvard’s plan since the order was released after Harvard announced their plans for the Fall (Harvard and MIT have since sued ICE, a move supported by many universities nationwide). However, we did want to check if international students’ opinions of the plans were notably different from their peers’.

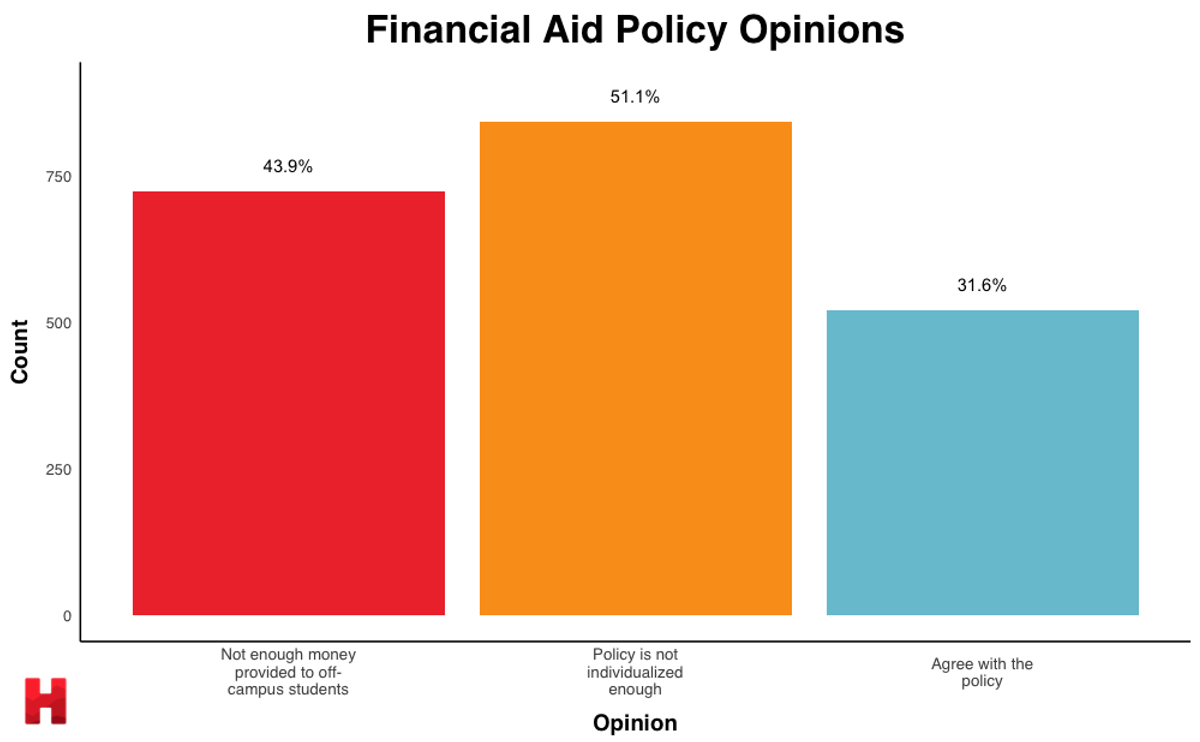

We also wanted to gauge reactions to the plan’s accommodations for students on financial aid. Harvard announced that enrolled, off-campus students on financial aid will receive $5,000 a semester (in lieu of traditionally receiving aid that covers dorm costs) for their living expenses.

Note that these percentages don’t add up to 100, since students could select multiple concerns (for example, that the money given should be increased and individualized).

53 percent of our respondents reported being on some form of financial aid, matching almost exactly the 55 percent of students at the College on some aid. Financial aid policy opinions among students on financial aid matched the opinions of the overall sample.

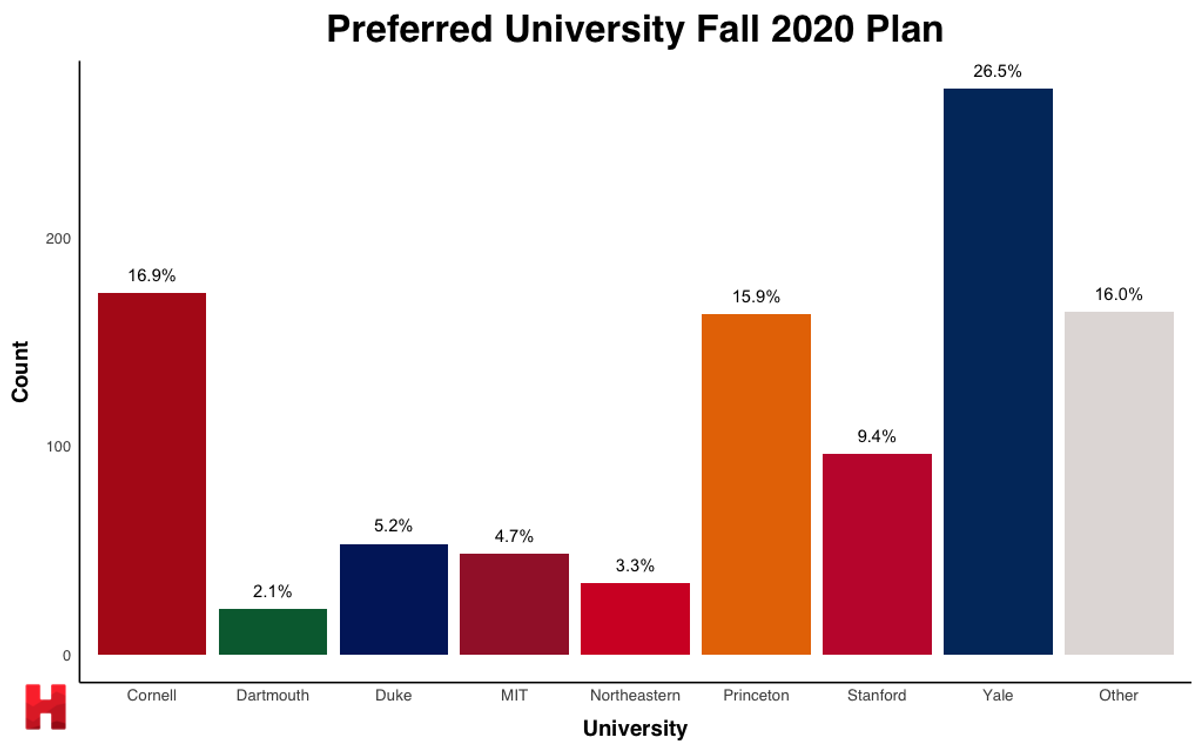

In our last analysis of COVID-19 at Harvard, a majority of students favored a fully on-campus semester, but a plurality of respondents also said that if they were administrators, they would only allow some students on campus, which is what administrators actually did.

Now that Harvard and many of its peer colleges have concretized plans, we wanted to see which fully fleshed-out plan students preferred. Many other Boston-area and Ivy League institutions are allowing more students on campus at a time and are allowing each class year back at some point.

Yale announced a hybrid remote and in-person instructional model, with almost all undergraduate classes to be remote. First-years, juniors, and seniors will be allowed on campus in the Fall, and sophomores, juniors, and seniors in the Spring, maintaining a 60 percent campus density compared to Harvard’s 40 percent. Cornell will welcome its entire undergraduate body back to campus in the Fall, also with a hybrid learning model. Both universities will impose social distancing rules on residential students.

Finally, we asked students for their qualitative thoughts on the policy and gave them a long-form answer box to reply.

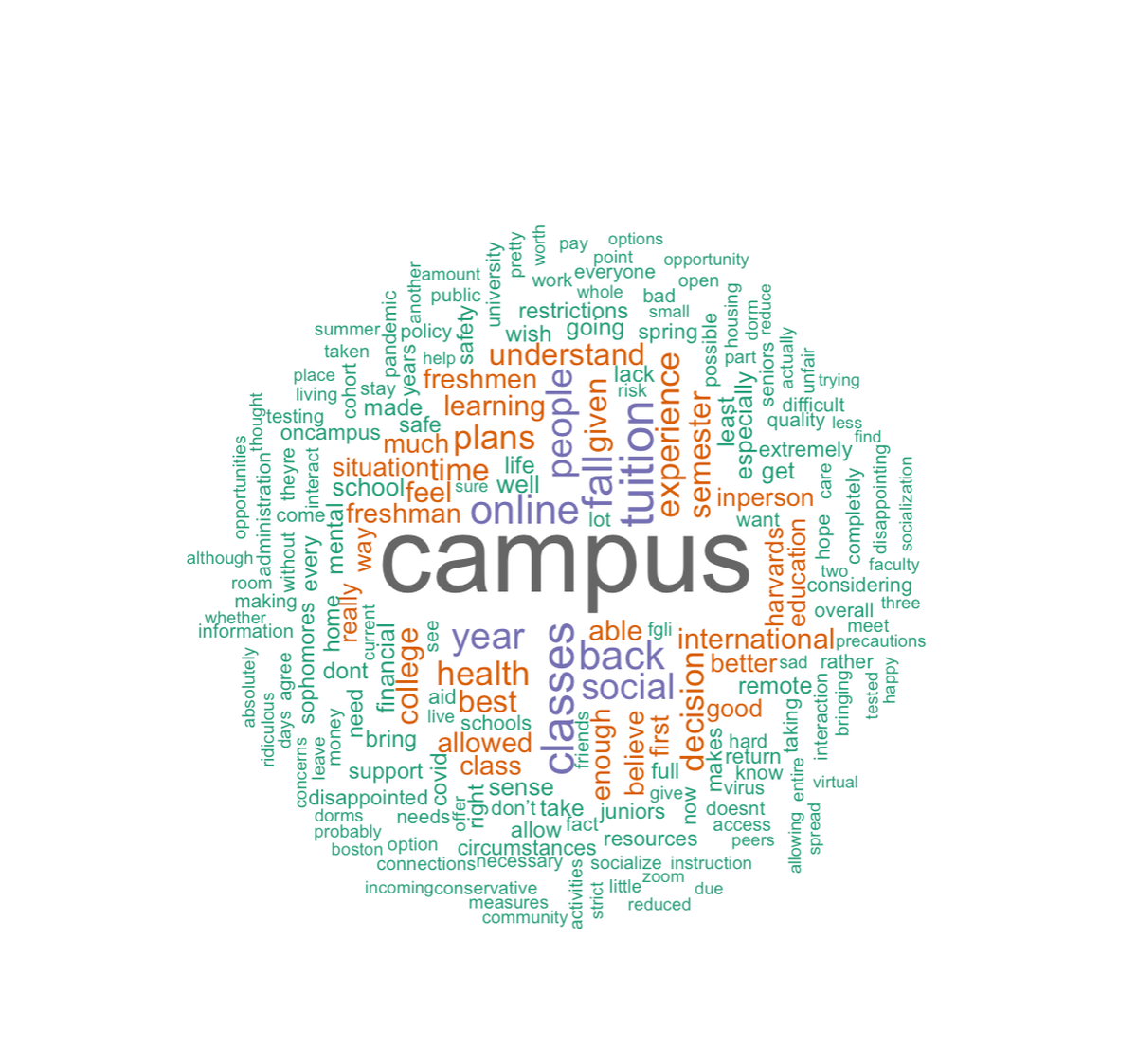

A cloud of the most frequent words in students’ free-text responses. Common words such as “the” and “and” were removed, as were “students” and “Harvard.”

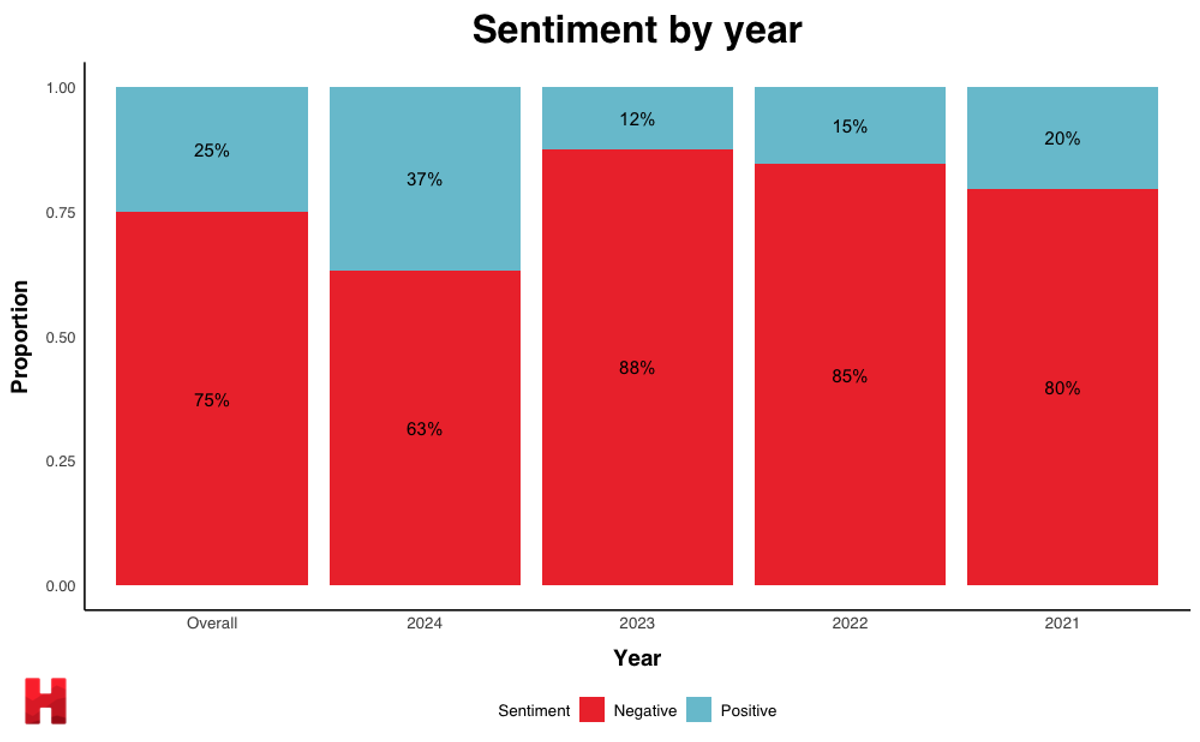

A cloud of the most frequent words in students’ free-text responses. Common words such as “the” and “and” were removed, as were “students” and “Harvard.”We performed a sentiment analysis of the comments using a PyTorch Transformer to gauge whether they were positive or negative. Three quarters of responses to Harvard’s policy were classified as negative, with first-years generally more positive than upper-class students. However, it is important to note only around half of respondents left a comment, and that those leaving a comment likely also had the strongest feelings about the policy.

Sentiment analysis by Asher Noel

Sentiment analysis by Asher NoelSample Representativeness

We want to be transparent about the representativeness of our survey sample: We emailed the survey to undergraduate students in the classes of 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024. We had 1766 respondents. 54 percent of respondents reported being on financial aid, and 13 percent were international students, compared to 55 percent of students and 12 percent of students in the College overall, respectively.

The racial and ethnic demographics of our respondents roughly match that of the College, though Black students were underrepresented by about 4 percentage points (10 percent of our sample compared to 14 percent of the College).

The most significant skew in our data was an overrepresentation of incoming first-years. Members of the class of 2024 comprised about 38 percent of our sample while comprising around a quarter of the student body overall. The proportions of sophomores, juniors, and seniors were roughly equal. To account for this, we re-weighted our data for visualizations in which we saw differences by year, such as enrollment, so that first-years accounted for a quarter.

Final thoughts

It is fair to say that Harvard’s policy is not what most students were hoping for, but it’s also fair to say that with COVID-19, the semester could never be normal. Students are in for another semester of major disruptions to their learning, friendships, and college experiences. We are facing an unprecedented number of students planning to take time off to wait out the worst of the pandemic’s effects.

If students cannot return to campus for the Spring semester, many will have lost more than a quarter of their college career to COVID-19. And even if students are allowed back in the Spring, it will be a very different campus than the one they left in March 2020.

We are extremely grateful to the many students who filled out our survey, without whom this analysis would not have been possible. For students who are considering petitioning to live on campus, the deadline is tomorrow, Monday, July 13th. The non-binding deadline to decide to enroll or take a leave for the Fall semester is July 24th.

We hope that our analysis here has helped inform the Harvard community and will assist them as they continue to plan for the Fall semester.