A Look into Language Learning at Harvard

We explore all trends and tidbits related to the College’s language requirement: what courses are taught, and how many students enroll? How have these numbers changed over time? And what about the professors who teach them?

Introduction

All students at Harvard College are required to fulfill the Language Requirement: at minimum, two semesters worth of courses in a language other than English. Although some students are able to test out of the requirement, many opt to take classes, with some even pursuing a citation in a language of their choice. We were curious about all things languages: how many students, languages, classes, and above all… what trends or interesting tidbits could we find in the data?

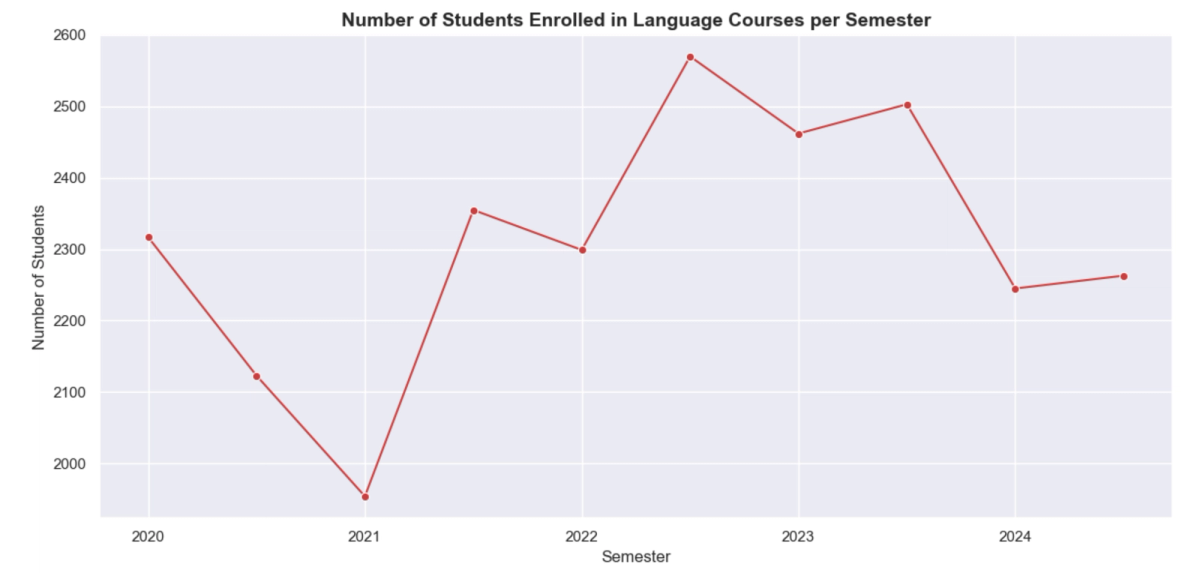

Our data was taken from the Harvard FAS Registrar’s Enrollment Reports across the past ten semesters (Spring 2020-Fall 2024), which we cleaned and combined into one large dataset with just courses teaching languages. Since the pandemic, 235 professors have taught 3,445 language classes for 87 unique languages. On average, 2,300 students took a language course each semester, with that number peaking at 2,575 in the fall of 2022. In the spring of 2021, however, only 1,956 students took a foreign language, a number far lower than any other semester.

Figure 1: Number of students enrolled in a language course, broken down by semester. The early stages of the pandemic saw a drastic decline in the number of students taking language courses, but this quickly rebounded after Harvard classes came back in-person.

Figure 1: Number of students enrolled in a language course, broken down by semester. The early stages of the pandemic saw a drastic decline in the number of students taking language courses, but this quickly rebounded after Harvard classes came back in-person.Analyzing the Language Departments

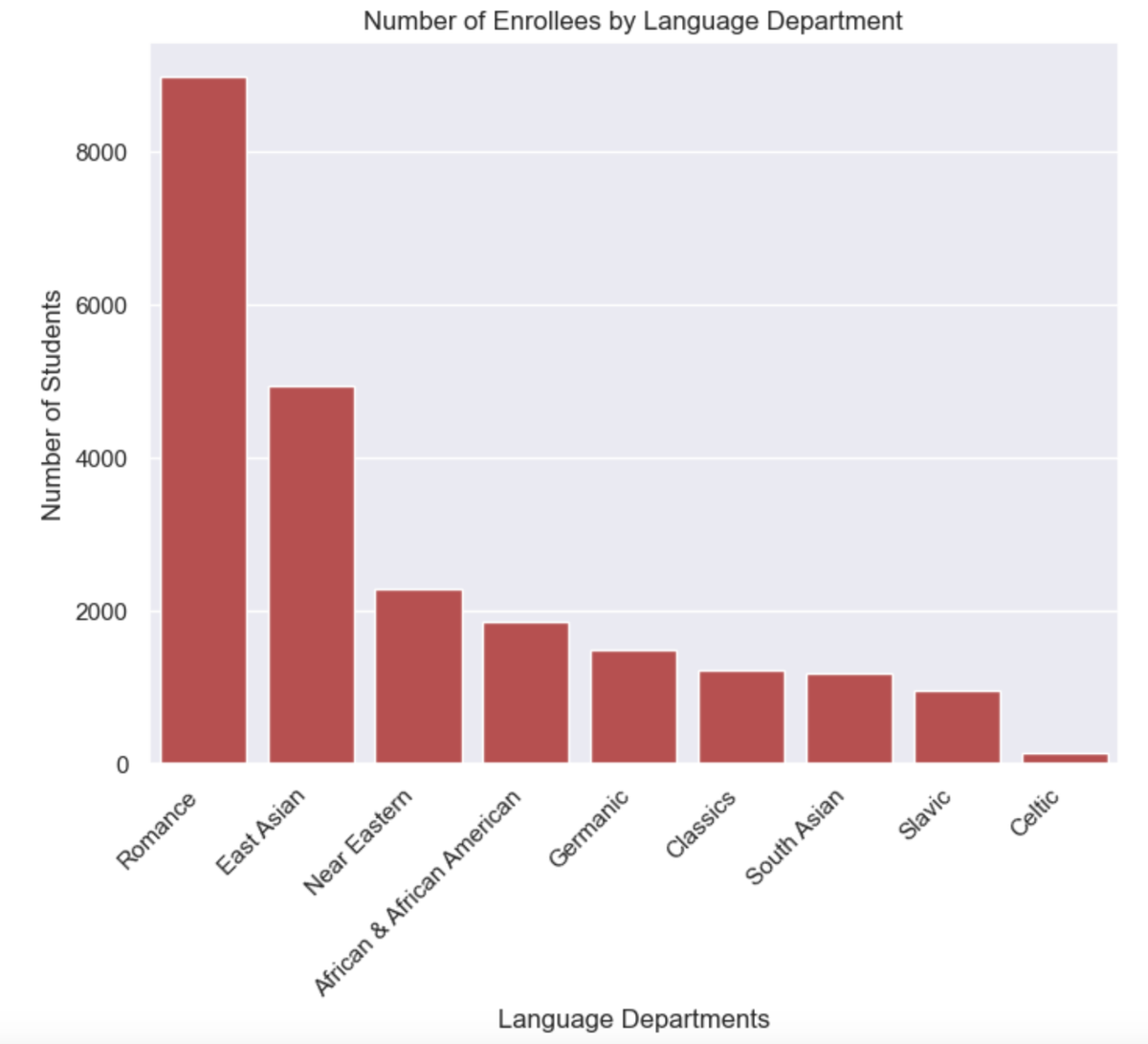

At Harvard, nine departments currently offer language courses, these being: African & African American Studies, Celtic Languages & Literatures, Classics, East Asian Languages & Civilizations, Germanic Languages & Literature, Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, Romance Languages & Literature, Slavic Languages & Literatures, and South Asian Studies. The Romance Languages department is easily the largest, having around 80% more enrollees than the next largest department (East Asian Languages) and 60 times more than Celtic Languages, Harvard’s smallest language-offering department.

Figure 2: Number of students enrolled in each language department across the past ten semesters.

Figure 2: Number of students enrolled in each language department across the past ten semesters.

However, it’s interesting to note that the departments with the most enrollees do not correspond to the departments with the most number of languages offered. The Romance Languages department offers six languages, only tying for the fourth-most offering of the nine departments. The African & African American Studies and Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations departments easily outpace all others in number of languages offered over the past ten semesters, with 25 and 17 unique languages respectively. All other departments have taught less than ten languages each during the same time period, with Celtic Languages & Literature offering just four.

The African & African American Studies and Near Eastern Languages departments have offered so many more unique languages than the other departments largely because unlike other departments, they constantly add (and sometimes remove) languages, with some running for just a few semesters and others thriving since introduction. Since the pandemic, five languages have appeared for a single semester before disappearing: Aramaic, Ladino, Shona, Pulaar, and Kimeru. The latter three languages all belonged to the African & African American Studies Department. That’s not to say that other language departments haven’t added more languages—among others, the South Asian Studies department introduced Filipino and Indonesian in spring of 2023, and the Slavic Languages & Literature department began offering Georgian in spring of 2022.

As for this past semester, the fall of 2024 saw the disappearance of West African Pidgin, Gullah, Aramaic, and Sudanese but the reintroduction of Syriac, Kinyarwanda, Chagatay, and Somali.

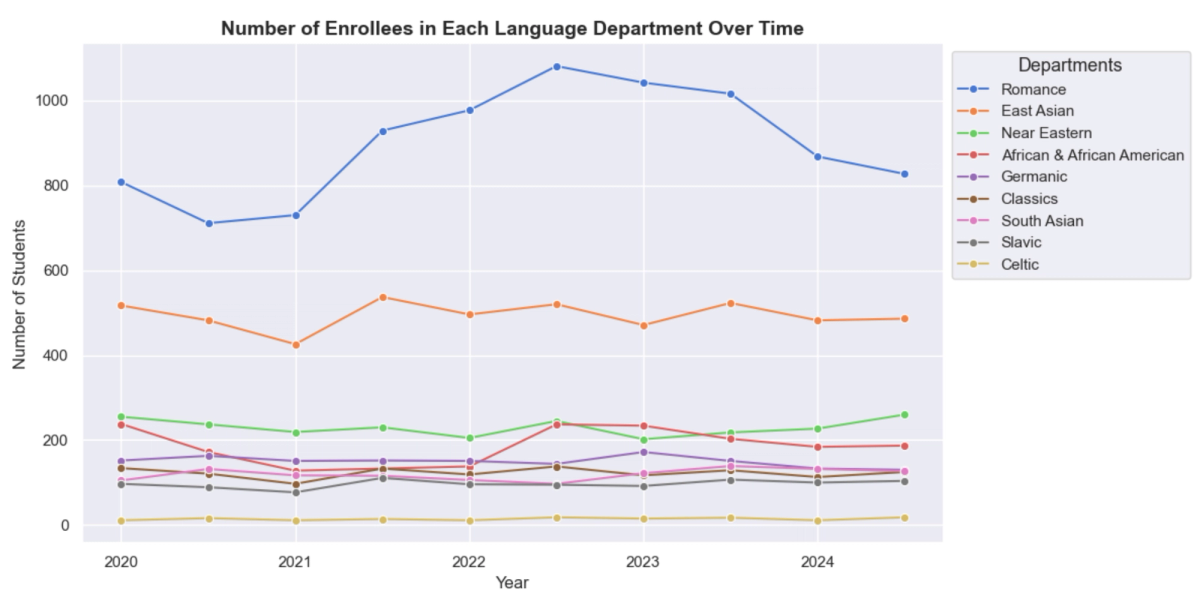

The data thus far gave us a good idea of how many students were in each language department on the aggregate, but we wanted to investigate further—so, we analyzed semester-by-semester differences for each department’s enrollees and number of classes offered.

Figure 3: Number of students enrolled in each language department by semester

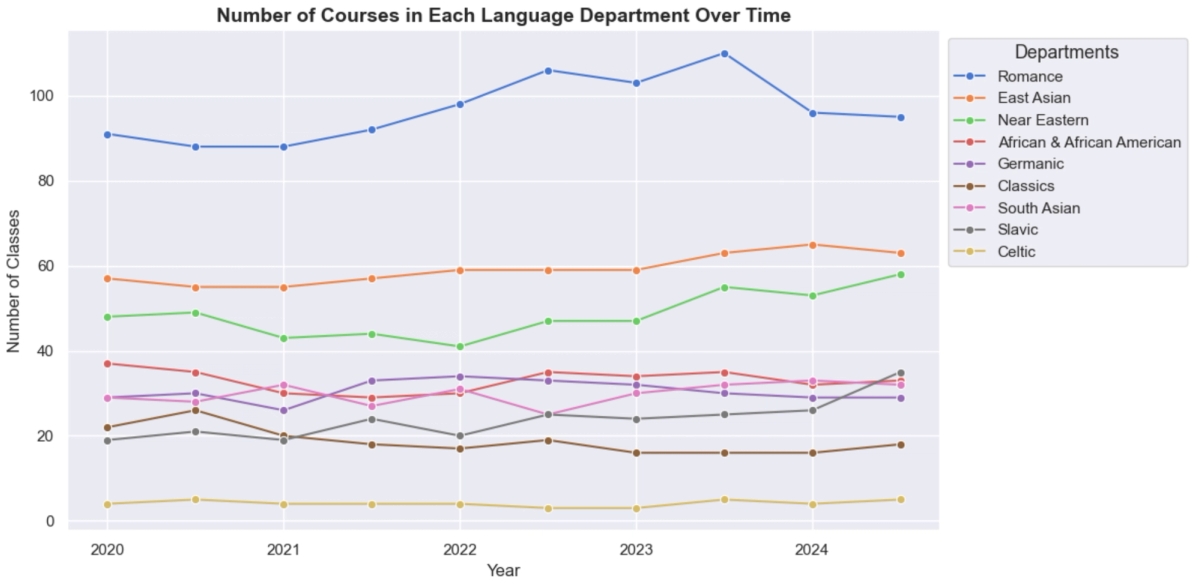

Figure 3: Number of students enrolled in each language department by semester Figure 4: Number of courses in each language department by semester

Figure 4: Number of courses in each language department by semester

Overall, the number of language courses in each of the nine departments has remained relatively constant, with the three largest departments (Romance, East Asian, and Near Eastern) and the Slavic language department showing increases on the whole over the past ten semesters. The only department with a decreased number of language courses on the whole is Classics, with Greek and Modern Greek decreasing in course options and Medieval Greek disappearing altogether after 2022. Even as the number of enrollees fluctuated greatly, the number of classes offered was generally more stable, with the South Asian Studies department even increasing their course offerings as total enrollment across languages dropped by 350 people between fall 2020 and spring 2021. When language enrollment rebounded the following semester, it was the two largest departments by enrollment (Romance and East Asian Languages) that saw the largest percent increases.

Overall, the number of students in a language per semester appears to correlate somewhat with the number of classes said language offers. Some departments, like the Romance Languages after the pandemic, have their course offerings mirror the number of students enrolled pretty closely. Conversely, the Near Eastern languages offer an abnormally high number of classes compared to students enrolled than the other departments, whereas Classics has very few classes compared to the other midsized departments despite having similar enrollment numbers.

Can Number of Classes Predict Enrollment?

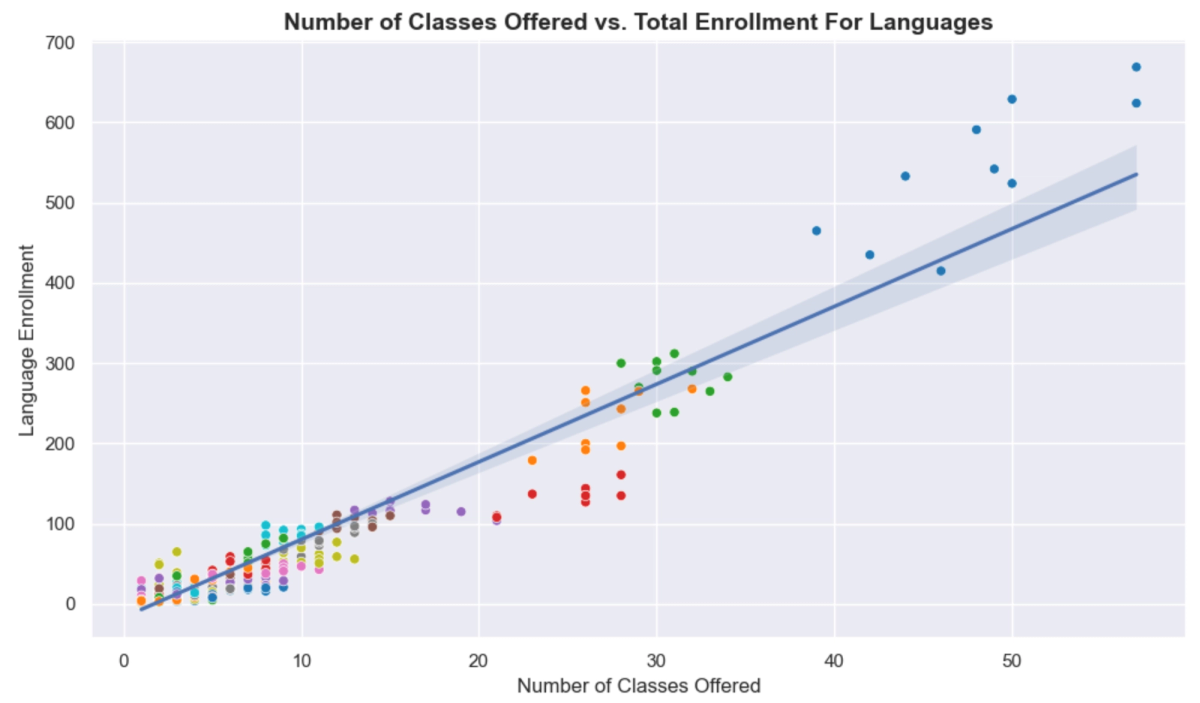

Although the relationship between the number of courses a specific language offers doesn’t seem to predict language enrollment too well, we decided to actually test it. Contrary to our initial beliefs, the number of classes offered by a language in a given semester is a good predictor of the total enrollment for that language.

Figure 5: Every language’s courses offered per semester against its total enrollment (also per semester). Different colors denote different languages.

Figure 5: Every language’s courses offered per semester against its total enrollment (also per semester). Different colors denote different languages.When plotted using a least-squares regression model, the number of classes offered by a language seems to explain 92% of the variation in total enrollment, with the main outlier being Harvard’s most popular language, Spanish (the blue data points in the top right of the graph). In particular, the data suggests that Spanish has much larger class sizes than other languages. By the clustering of points on the left side of the graph, we can also see that the vast majority of languages offer less than 15 courses per semester and have below 100 enrollees, with only four different languages (Spanish, French, Chinese, and German) consistently offering more than 20 courses a semester.

How many courses and languages do professors teach?

After looking into the students in each language, language department, and as a whole, we were curious about faculty—how many courses and languages do they normally teach?

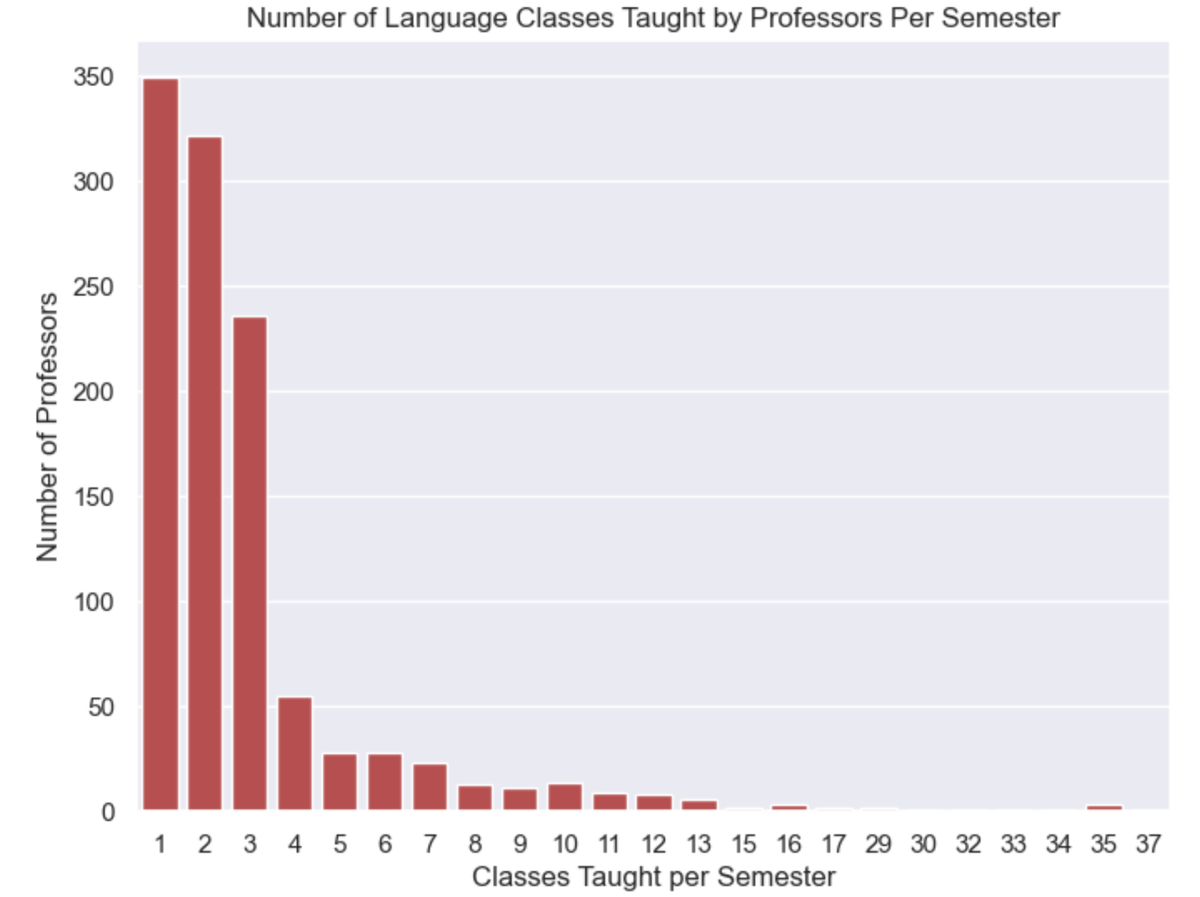

Figure 6: How many professors teach a certain number of courses per semester (these could be the same course taught in multiple classes or two courses from completely different languages).

Figure 6: How many professors teach a certain number of courses per semester (these could be the same course taught in multiple classes or two courses from completely different languages).

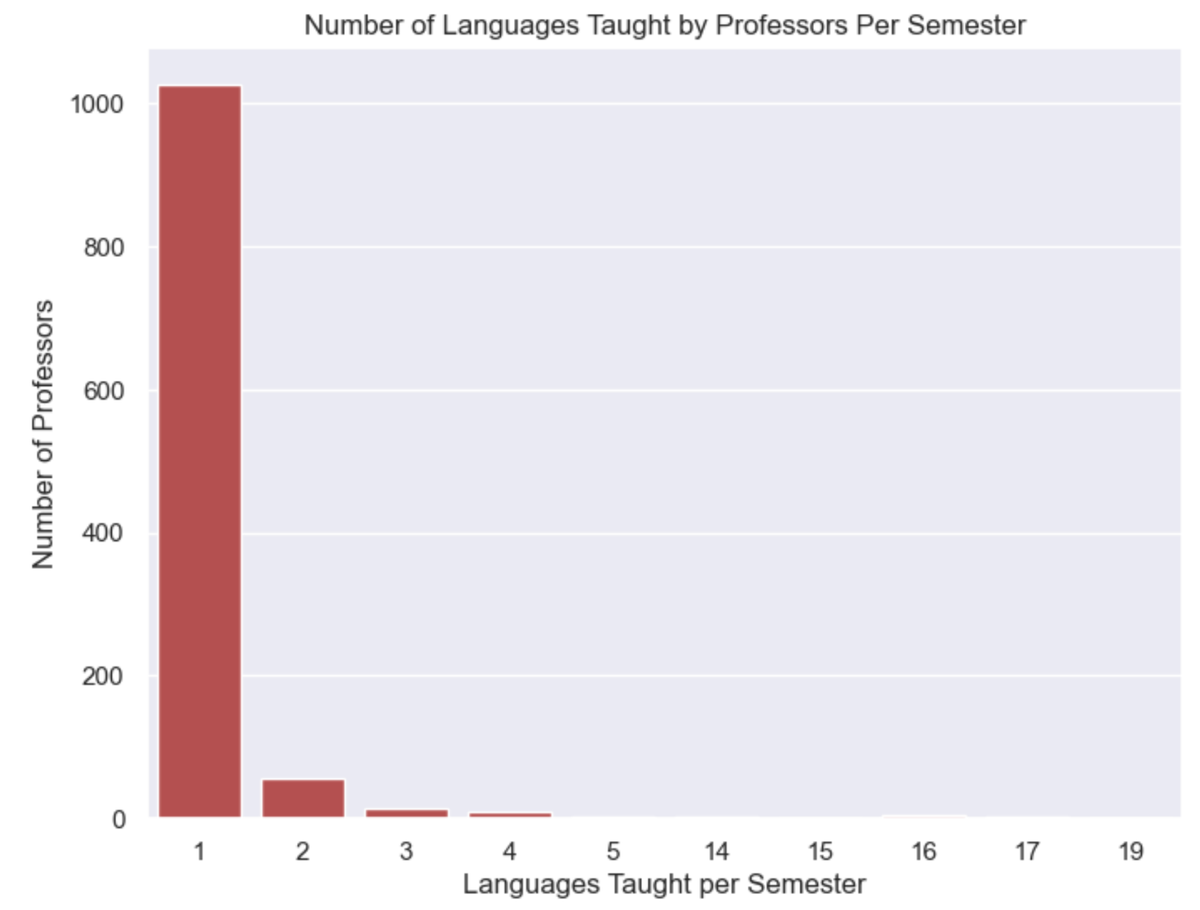

Most professors will only teach one or a small handful of classes, but there is still a pretty sizable number who teach up to 10 classes per semester. Not to mention that one professor has taught 37 courses in a single semester! Looking now at the number of distinct languages taught by each professor per semester, we see that most professors specialize in a single language.

Figure 7: How many professors teach a certain number of languages per semester.

Figure 7: How many professors teach a certain number of languages per semester.

Even moreso than classes, professors overwhelmingly choose to teach a single foreign language, indicating that most professors who teach multiple courses are likely doing so within a single language. Within both of these graphs are curious outliers. Who is teaching 37 classes a semester? Who is teaching 19 distinct languages… in a single semester?

As it turns out, pretty much all of the most extreme outliers in the data—language classes above 17 and number of languages above 5—corresponds to Professor John Mugane of the Department of African & African American Studies. He has single-handedly taught nearly 10% of all language courses and 30% of all distinct languages offered at Harvard over the past ten semesters. In an average semester, he teaches 33 courses and 16 languages, from Afrikaans to Jamaican to Zulu. He has headed at least one class for all 25 languages offered by his department in the past ten semesters (recall that his department offers the greatest number of unique languages out of any at Harvard, and it’s not close). Of the 330 language courses offered by his department since the pandemic, his name is attached to 329 of them. This does not necessarily mean that Mugane is personally teaching all of these courses—for instance, the student comments in the QReports Harvard’s Elementary Afrikaans courses (AFRIKAAN AA and AFRIKAAN AB) indicate that Adriaan Steyn and Juffrou Lynn have been the main course preceptors. Still, as the Director of Harvard’s African Language Program since 2003, Professor Mugane has undoubtedly played a central role in its development—he is the reason Harvard gets to boast having “one of the largest [African] language programs in the world.”

Additionally, Professors Parimal Patil and Richard Delacey of the South Asian Studies department are similarly impressive, often teaching more than 3 languages and 10 classes per semester. Finally, Professors Adriana Gutiérrez, María Luisa Parra-Velasco, and Johanna Damgaard Liander have taught the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th most language courses at Harvard respectively since 2020 (following, of course, Prof. Mugane). All three professors solely teach Spanish courses.

Conclusion

Our report offers a comprehensive overview of Harvard’s language offerings, including the breadth of departments and courses offered; the change of courses and enrollment over time; and the workload of faculty members teaching language courses. While our results display a large range of department sizes and enrollments, it also provides key insight into the relationship of these two variables, with the number of courses predicting enrollment for each language department reasonably well. The outliers we found when analyzing professors’ workloads also highlight the role of faculty dedication in expanding the offerings (and by extension enrollment numbers) of smaller language departments. We hope that our findings will spark more discussion and interest in one of Harvard College’s most foundational requirements.

GitHub repo with raw/cleaned data and analysis: here